Când un scriitor are succes, sar toţi confraţii pe el. Nu ca să-l felicite, ci ca să-l ţină de mâini. Dacă are succes de librării, e un idiot care scrie chestii comerciale. Dacă are recenzii bune, e doar un piarist excelent, fără strop de talent scriitoricesc. Dacă ia premii, se declanşează o adevărată dramă naţională: se zguduie internetul de opinii negative, pozele nenorocitului scriitor sunt transformate în caricaturi, numele lui e aşezat, cu toată condescendenţa, la coada clasamentelor. Cei mai energici dintre denigratori se dedică imediat cauzei şi pun în mişcare trupele de nemulţumiţi, care fierb de multă vreme în fierea proprie, aşteptând momentul potrivit pentru a se exprima. Liderii războaielor sunt întotdeauna neobosiţi şi inventivi. Ei alcătuiesc cu probitate listele de înjurături, le distribuie şi iau toate măsurile ca lucrul să fie dus până la capăt. Se ridică imediat o căpetenie, care îl sună pe scriitor ca să-l întrebe dacă este la curent cu înjurăturile respective, apoi, pentru siguranţă, îi trimite o copie a celor mai alese invective, prin e-mail, SMS, şi prin poşta normală, eventual, printr-o scrisoare cu confirmare de primire.

Când un scriitor are succes, sar toţi confraţii pe el. Nu ca să-l felicite, ci ca să-l ţină de mâini. Dacă are succes de librării, e un idiot care scrie chestii comerciale. Dacă are recenzii bune, e doar un piarist excelent, fără strop de talent scriitoricesc. Dacă ia premii, se declanşează o adevărată dramă naţională: se zguduie internetul de opinii negative, pozele nenorocitului scriitor sunt transformate în caricaturi, numele lui e aşezat, cu toată condescendenţa, la coada clasamentelor. Cei mai energici dintre denigratori se dedică imediat cauzei şi pun în mişcare trupele de nemulţumiţi, care fierb de multă vreme în fierea proprie, aşteptând momentul potrivit pentru a se exprima. Liderii războaielor sunt întotdeauna neobosiţi şi inventivi. Ei alcătuiesc cu probitate listele de înjurături, le distribuie şi iau toate măsurile ca lucrul să fie dus până la capăt. Se ridică imediat o căpetenie, care îl sună pe scriitor ca să-l întrebe dacă este la curent cu înjurăturile respective, apoi, pentru siguranţă, îi trimite o copie a celor mai alese invective, prin e-mail, SMS, şi prin poşta normală, eventual, printr-o scrisoare cu confirmare de primire.

Asta se întâmplă cu scriitorii care iau premii naţionale.

Vă întrebaţi poate ce se întâmplă cu cei care au succes internaţional. Cu ei lucrurile stau cu totul diferit. Pentru scriitorul de succes internaţional există două etape distincte.

În primul rând, se alcătuieşte o unitate de gherilă, care se străduieşte să închidă principalele trasee ale succesului. E-mail-urile încep să curgă, intrigile se ţes cu viteza netului, iar ostaşii cei mai devotaţi sunt trimişi în primele rânduri. Există întotdeauna un coordonator al serviciilor de informaţii, care are un pluton de blogeri, o piaristă, gata să-şi dea viaţa pentru el, şi un telefon gratuit. Se fac listele cu oferte pentru soldaţi – în premii, în cărţi publicate peste noapte, în rubrici tv şi, nu în ultimul rând, în funcţii şi în subvenţii, desigur, din buzunarul comun. Niciun sacrificiu nu este de ajuns pentru o cauză dreaptă. Un scriitor ieşit la rampa internaţională e împiedicat pe toate căile. I se ia urma şi toţi factorii implicaţi în oprirea agitatorului sunt puşi în mişcare cu o solidaritate totală şi patriotică. Diaspora este pusă la curent cu această stare scandaloasă: un impostor riscă să ne facă ţara de râs. El trebuie oprit, îngenuncheat, înlocuit pe loc cu un alt scriitor, devenit peste noapte extrem de important. Sunt reziliate contracte şi amânate tunee, în numele câte unei bine plasate gogoriţe, de genul că publicarea ori promovarea nenorocitului va declanşa un scandal fără precedent: e antisemit, e pedofil, a colaborat cu Securitatea, e spion. În cartea lui îşi bate joc de toată Europa. Iar editorii europeni iau foarte în serios astfel de ameninţări, mai ales că un zvon poate să terfelească repede orice pasiune.

Dacă, în ciudat acestei bătălii susţinute, totuşi scriitorul reuşeşte să-şi câştige notorietatea literară, toate ostilităţile mor instant. Lumea, până atunci luptătoare, cade la picioarele lui, iar atrocii atacanţi se transformă pe loc în linguşitori pe viaţă ai marelui învingător.

Acesta este traseul obişnuit al scriitorului român.

Mulţi scriitori de talent şi-au dat toată energia pentru a-şi ţine confraţii de mâini, iar această operaţie epuizantă le-a mâncat timpul, energia şi dragostea de scris, încât n-au mai apucat să dea marea operă la care visaseră ei înşişi.

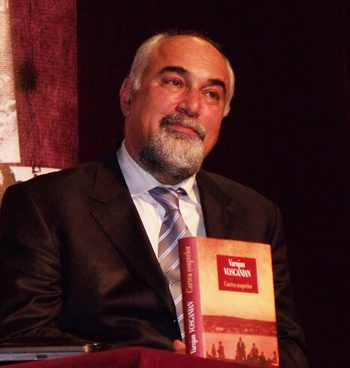

Varujan Vosganian a scris o singură carte (Cartea şoaptelor) şi-a şi fost propus pentru Premiul Nobel. Această întâmplare nu putea să treacă neobservată.

Cazul lui este însă diferit. Ministru, senator, vicepreşedinte al USR, avea mijloacele să lupte împotriva eventualilor denigratori. Dar nu până la capăt.

Cartea şoaptelor a plăcut chiar de la apariţie, scriitorimea recunoscând că este un roman frumos, scris cu simţământ. Cartea narează, la persoana I, povestea unei familii şi istoria armenilor. Cele mai memorabile pagini se referă la genocidul pus la cale de o formaţiune extremistă turcă (1915-1922), soldat cu moartea a 1.500.000 de armeni. Mulţi au fost obligaţi să plece în deşert, spre Siria, într-un marş al morţii, tragedie care n-a fost niciodată recunoscută de către statul turc. Circumstanţele care au generat această stare de fapt sunt specifice Europei de după Primul Război Mondial, care a sfărâmat imperiile şi a schimbat fundamental harta Europei. Anatolia, populată de turci, greci, armeni etc, a intrat în nou formata Republică Turcă, ceea ce a declanşat un adevărat program de epurare etnică din partea turcilor.

Varujan Vosganian descrie drama armenilor din Anatolia, ucişi sau izgoniţi, ceea ce a conferit cărţii sale şi o miză politică. Tradusă în mai multe limbi, promovată, a stârnit entuziasm în comunităţile de armeni şi nu numai. În 2012, Uniunea Scriitorilor din România a propus romanul pentru Nobel. Acelaşi lucru l-a făcut şi organizaţia similară a armenilor. Apoi, în mod neaşteptat, Asociaţia Scriitorilor de limbă ebraică din Israel a propus Cartea şoaptelor la Premiul Nobel. Cu toate că există mai mulţi scriitori evrei de top, forumul lor suprem l-a ales pe Vosganian. Versiunea ebraică a cărţii se pare că a sensibilizat, mai ales prin tema genocidului. (Pentru cine vrea să citească mai mult, vedeți cum sună propunerea scriitorilor evrei* la finalul articolului.)

Pe lângă reacţiile comunităţilor scriitoriceşti, au urmat şi reacţii politice. Guvernul turc a protestat oficial, cerând Guvernului României să nu promoveze cartea, considerând-o ofensatoare pentru turci. Astfel de nemulţumiri legate de cărţile de ficţiune sunt frecvente şi ele, de regulă, promovează cartea. Nu şi de data aceasta.

La scurtă vreme după ce Varujan Vosganian a fost pus pe lista pentru un posibil Nobel, a şi fost pus sub acuzaţie. S-a spus că în anul 2006 a subminat economia naţională şi de aceea a şi fost deferit Parchetului.

În lumea noastră politică, populată de seraliştii epocii comuniste, Varujan oricum era o ciudăţenie. Cine mai ţine minte că a fost coordonatorul programului de guvernare în 2004? Că a contribuit la cota aia unică de impozitare, de care ne bucurăm toţi? Că a adus Fordul în România? Că a facilitat existenţa Delphi Diesel Systems, la Iaşi, ori Parcul Tehnologic de la Titu? Sunt, oricum, fapte foarte palide în comparaţie cu bătăile din parlament, înjurăturile şi beţiile memorabile ori cu palatele aurite ale altor parlamentari. Prin comparaţie, Vosganian e un domn educat, care crede încă în forţa exemplului personal. Ceea ce trebuie să recunoaştem e un pic cam anacronic.

De Vosganian am auzit prima oară de la un poet bolnav fără speranţă, dar care spera încă într-o minune. Cineva l-a sunat pe Vosganian, care a şi răspuns, spre marea mea uimire, sărind imediat în ajutorul confratelui nostru. După aceea am avut de multe ori prilejul să constat că e un politician atipic, care răspunde întotdeauna la telefon. Mai mult decât atât: nu refuză pe nimeni, nu rămâne indiferent la suferinţa celorlalţi. Îşi plăteşte datoriile. E un om de cuvânt, generos şi luptător. Are entuziasm, are compasiune. Sunt puţini scriitorii care să nu fi fost ajutaţi de el. Şi toate astea într-o lume sufocată de oportunişti.

Habar n-am în ce constă vinovăţia lui presupusă, însă, cu moştenirea lăsată mie de strămoşi, am puţină încredere în justiţia românească. În ultimii ani am asistat deja la multe erori şi aberaţii, chiar pe această temă a acuzării unor personalităţi de top. Regizorul Andrei Blaier a fost acuzat public de colaborare cu Securitatea comunistă. Ziarele l-au terfelit, prietenii l-au blamat, iar Blaier a şi murit din cauza aceasta. La puţină vreme după aceea, el a câştigat post mortem procesul împotriva acuzatorilor, dovedindu-se că acuzaţiile nu erau adevărate şi că de fapt a fost hărţuit de Securitate non stop. Însă nimeni n-a mai scris despre aceasta. Iar cazul său nu este unul izolat. Presa din ultimii 10 ani a înregistrat un număr impresionant de acuzaţii retrase ulterior, prin adeverinţe de” necolaborare cu Securitatea”. Însuşi Varujan Vosganian a fost acuzat că e spion (cazul Turcu), dovedindu-se în instanţă că totul a fost doar o calomnie. Prin urmare mi-e greu să vorbesc despre acuzaţiile care i se aduc cuiva care ajunge peste noapte persona non grata. Certitudini nu sunt decât că Vosganian e un om onorabil şi un scriitor bun. Restul sunt întâmplări care se leagă în mod evident de ţesătura obişnuită a vieţii noastre româneşti. În plus, povestea ridică suspiciuni şi prin altceva. Vosganian este pus alături de Videanu (cel cu bordurile)! Această alăturare seamănă cu ironiile marinăreşti, din start făcându-mă să n-o iau în serios.

Şi există şi această plasare temporală mai mult decât dubioasă: acuzaţiile aduse lui Vosganian au început exact după ce a fost propus pentru Nobel. Or, cunoscând cum funcţionează ambiţiile scriitoriceşti, mi-e greu să cred că în aceste acuzaţii nu sunt amestecaţi confraţii noştri, scriitorii. Mai ales cei băgaţi în politică, nu foarte puţini.

Povestea lui Vosganian începe cu succesul accelerat al unei cărţi, continuă cu protestul turcilor, cu propunerea pentru Nobel, şi culminează cu nişte acuzaţii extraliterare, al căror rol, în opinia mea, nu este de a elimina un politician, ci de a scoate din circuit un scriitor, ajuns foarte aproape de consacrarea internaţională. Dacă citeşti ce-a scris presa internaţională, comparându-l, de exemplu, cu Marquez, este imposibil să nu vezi imediat şi feţele confraţilor luptători, înverzite de invidie. Ce alt scriitor român a mai avut asemenea presă? Mi-e greu să cred că treaba cu subminarea economiei nu are legătură cu succesul literar. Viaţa noastră literară este puternică şi bazată pe cele mai ridicole ambiţii.

***

* Herzel Hakak, January 29, 2013

To: The Nobel Prize Committee

Stockholm

Esteemed members of the Nobel Prize Committee,

We would like to nominate the Romanian writer Varujan Vosganian as our proposal for the 2013 Nobel Prize for Literature, on the basis of his literary work, and especially for his most recent novel, “The Book of Whispers”. These days, the world is marking 100 years since the Armenian genocide- and its impressive literary documentation in “The Book of Whispers” by Varujan Vosganian transforms itself into a Yahrzeit candle of this unbearable genocide.

Vosganian has molded the Armenian genocide into a true testimony, and “The Book of Whispers” that he has written will remain a live monument. In this pain memorial, the author has brought to life all the memories, all the bloody moments, all the shattered hopes. The lifeless past rises above the debris. Vosganian has joined, with his impressive literary achievement, the ranks of the classic writers who were able to give to the world great epic works such as “War and Peace”, “Anna Karenina” and others. Amongst these works, one must not forget also Franz Werfel’s novel, “The Forty Days of Musa Dagh”- and thus we have acquired another fiery declaration that describes the story of the Armenian refugees’ travels, suffering, pain, hope and lack of hope. The Armenian genocide bursts in “The Book of Whispers” as a flame, and, in the writer’s stroke of the pen, the saga of the generations shines brightly in compassionate and human spirited nuances. “The Book of Whispers” utters and recounts the story, while its strength appeals to every human being.

It is true, it is mainly a story of the sufferings of the Armenian people, and the pages of the book picture, with an artist’s eye and through the different angles of the death marches, the illustration of the corteges on the path to death, of the testimony of those horrible years. Past forces and terrors gush out in the year of terror 1915- this is the beginning of the period of extreme fright. The mass-murder of a million and a half souls. A world that rotates around its own axis.

After I have read “The Book of Whispers”, the Armenian genocide pictures itself to me in a different light, it becomes a whisper, that has metamorphosed into a cry, the echo of which crosses the earth from one end to the other, in a quest to change the whole world as we know it.

The literary techniques utilized by the writer are various, and through them he succeeds in touching the reader’s heart, in keeping the dramatic tension every moment and in intensifying the reader’s empathic side with the characters. The writer knows how to make the connection between the past and the present, between the sacred and the profane. The title, “The Book of Whispers”, represents, in the main text, a secret encoding, a concealed notebook, in which the Armenian genocide is recorded from inside the community, from the intimacy of those who suffer. Fragments of allusion to the hidden notebook bring to light, in front of our eyes, the essence of the genocide: this is the holy book, the one in which history acquires not only dates and names or winners and losers, but also significance- and in this structure a special place is occupied by the photographs. The author writes: ” In The Book of Whispers photos often take the place of the living human beings”. Further down, after a few lines, Vosganian shares with us another secret from that mysterious book of whispers: “The Armenians, sitting in their decimated circle, used to fill the gap created by the departure of one of their own with his picture. Photographs became, for the Armenians of that time, a testament or a life insurance.” Throughout the book, pictures exert a vital force, like memorial candles, candles of testimony.

In the book there is no before and after, as the plot is not linear, but it is a stream of consciousness. The pages absorb us into the author’s family history, into stories depicting episodes from the world of the Armenian people, into universal historical events that describe the philosophy that lies beyond the facts, the real life above the dry, factual chronicles. There is another world, reflected by and apart from that of the novel which we are reading. In this world, we find the Book of Whispers, a world whose entire existence is comprised of a story within another story, memory within memory, character who crosses path with other character. Underneath all this construction there is a subsurface structure, composed solely of souls and dreams and hidden codes, and that is the place where the real structure lies. Because of this, the writer feels that it is important to be known that the historic data does not represent the book’s essence: “This book, although dealing mostly with the past, is not a history book, as in the history books the focus is, most often, on the winners; this is more a collection of psalms, as it deals with the defeated.”

The story of Mineas the Blind follows the main direction of the book, that is to bring forth and honour the role and significance of the shadow behind the light, the hidden reality. It should not come as a surprise to anyone that this blind man is the one who sees things better than all the others. Sometimes, he seems to be the metempsychosis of that Theresias from the Greek tragedy.

The cecity, the mystery and the dream govern the action of the book, and the compulsion of life is to keep searching and researching in order to get to the core of things, to that secret code of the universe. The author writes about his grandfather’s motto that he ” believed that the world exists to be understood…”.

“The Book of Whispers” by Varujan Vosganian, will forever be considered as the holy book of the Armenian genocide, as part of the holy scriptures, the scroll of the prophet of destruction, who foresees chapters from his people’s affliction, who tries to understand the secret of his ancestors’ existence, who follows closely the massacres committed by the Turks, the horrors taking place in the convoys of exiles, all this written in a restrained language, with a heartbreaking pain. The author attempts to explain the meaning of the events and why is it that they express themselves susurrously and not loudly. “This story, that we call the Book of Whispers, is not my story. Its roots go a long way back before my childhood years, when people would whisper their tales, instead of shouting them. It began a long time before it ever became a book. And it did not start in the Focsani (a town in Romania) of my childhood.

The whisper of the Armenian history resonates in a tormented way, the description of the massacre injures the fragile strings of the soul, it quivers the heart. “In Trabizonda… several hundreds of women, together with their children and the elderly who were unable to walk, were embarked on the rafts and taken offshore. Amidst all this misfortune, the women were glad when they were told that part of the trip would be made by boat, thus spearing them of another trouble. But, the next day, the rafts returned to shore empty.” And in a different fragment: “The Armenian children in the German orphanage were drowned in the near-by river. The women from Mesne, who were heading towards Urfa, were killed and dumped in the river. The massacred and mutilated bodies of the women lay for months on the road between Sivas and Kharput… One could still see their bones scattered there by the end of the first half of 1916.”

When we avidly read the chapters of “The Book of Whispers”, we feel that that “late child” understands perfectly both his lost childhood and the old age of his grandparents. He succeeds in acquiring the secrets passed on by his grandfather, thus taking in the spirit of the Armenian people and, most importantly- he succeeds in recounting the events that hover between memory and suffering, a story which he had witnessed, a story to be passed on to future generations.

Three outer narrations, like three satellites, straighten out the main narrative of the book- the life of the Armenian people. One of these outer narrations is that of the wooden horse, the writer providing the childhood of the boy who was not meant to have one, with a special significance. Even the childhood toy is granted several sequential stories, the tales of the wooden horses. The same toy is subjected to a metamorphosis that reflects the dream and its gradual shattering along the unfolding of the action. Another satellite, vital to the understanding of the characters, emerges under the shape of a different legend- the story of the funeral and the casket. In the description of this entombment all the characters are, symbolically, present and we are witnessing a gathering of the souls: we are enwrapped in this sequence that resembles an episode from the Book of Prophets, an episode in which a holy air seems to be hovering, an episode that reunites all the characters, whether living or dead. The third outer narration is that of the concentric circles, like a spotlight over the convoys of people, a human tale that purifies the tears and the appeasement with the suffering.

Varujan Vosganian’s book is like a funerary monument of the entire Armenian genocide. The writer succeeds in describing the essence of the catastrophe, the depth of humankind’s failure and that dirge that follows us in order to teach remembrance and for the world to know how to be in mourning and not to forget the executioners’ shame. The author specifies: “People’s history is the history of events, of memorable words, but it is, mostly, the history of regards. Hard to describe, hard to decipher, but even more intense and more real…And the photos of the weakened dead, with their staring gaze, are even more arresting as, while fading away because of hunger, fatigue or disease, their eyes still remained unscathed, appearing, on their diminished faces, huge and ravenous.”

Vosganian has written the testimony for the world to know what happened, for the world to remember what happened. The burden has been heavy, and Vosganian knows, in his way, that it is impossible to tell everything. “The Book of Whispers is an action that no one fully utters, as if each one was afraid to comprehend it all, thus trying to redeem their life from vacuity.” When the funeral is described, when all the objects and the gifts from the characters of the book are buried, we are witnessing a sacrosanct event, in which the casket is led to the burial ground. Here, the writer feels that he should add the moral: “And thus, once the casket was buried, it was proven that answers have the same mortal fate as humans, leaving room for life to follow its course.”

Life and remembrance, death and testimony – those are the essence of the book, and, in this way, it is created an extension of the scriptural verse “I shall not die, but live, and declare” (Psalm 118:17).

Awarding the Noble Prize for Literature to Mr.Varujan Vosganian will be both a formal recognition of his special and rare literary gift, and a testimony and a remembrance of the Armenian genocide. The Nobel Prize will represent a message to the world, a true acknowledgement and an appreciation from the entire literary community of Mr.Vosganian’s work; it will be a prompting for him to continue recounting, to persist in poetizing the spirit of the Armenian people, this noble melody that we are neither allowed to silence nor to forget.

With warm regards,

Herzel Hakak,

Chairman of the Hebrew Writers Association in Israel

Citiţi şi

A spune adevărul este cea mai bună glumă

Cum gândește Herta Müller: ʺNimeni nu te poate sili s-ajungi ori să rămâi așa cum ai fost crescutʺ

J. M. Coetzee – “Deschide-ți inima!”

Acest articol este protejat de legea drepturilor de autor. Orice preluare a conținutului se poate face doar în limita a 500 de semne, cu citarea sursei și cu link către pagina acestui articol.