De îndată ce începem să măsurăm timpul cu ceasuri, devenim obsedați folosind timpul în mod cât mai „eficient” posibil. Puteți vedea foarte clar asta din momentul în care orologiile au pătruns în oraşele Europei medievale. Dictonul „timpul înseamnă bani”, care sună atât de actual şi pare să definească modul în care trăim în secolul 21, a fost inventat de fapt de Benjamin Franklin, acum 250 de ani.

Mai târziu, când setea noastră de a folosi timpul eficient s-a ciocnit de revoluţia industrială (care ne-a oferit instrumentele pentru a face totul mai rapid) şi de capitalismul modern (care elogiază viteza în atât de multe instanţe), am pornit pe drumul care a condus la secolul 21, în care fiecare moment al zilei este o cursă contra cronometru, atât în viaţa privată, cât şi la serviciu.

În cultura noastră de tip fast-food, am devenit obsedaţi să stoarcem fiecare picătură de productivitate din timpul pe care îl avem la dispoziţie. Am început la serviciu, dar obiceiul a infectat şi modul în care ne comportăm în timpul liber. Chiar şi când nu suntem la muncă şi nu avem termene-limită sau şefi care să ne preseze, suntem îngroziţi ca nu cumva să pierdem timpul.

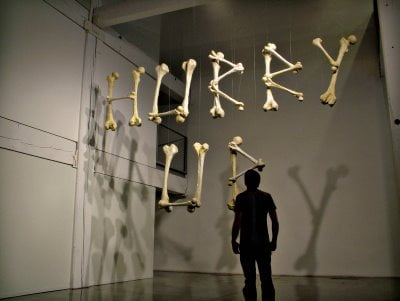

Iar asta înseamnă că ne simţim forţaţi să ne folosim timpul liber pentru a fi activi, productivi, pentru a face lucruri. Iar când nu o facem, ne simţim vinovaţi. Consecinţa este aceea că ideea de „timp liber” capătă un sens peiorativ. În limba engleză, oamenii se referă la el ca la un „timp mort” (dead time) sau „timp căzut” (down time). Prin asta vreau să spun că trăim cel mai bine când trăim din plin, când acordăm atenţie fiecărui moment şi fiecărei acţiuni. Între noi şi timp e o relaţie nevrotică. Îl vedem ca pe un huligan de care trebuie să ne temem şi care trebuie învins, sau ca pe o resursă limitată pe care trebuie să ne grăbim să o exploatăm cât mai repede posibil.

Asta ne conduce la a pune cantitatea înaintea calităţii. Sfârşim înghesuind activităţi şi surse de stimulare în program, cât să avem sentimentul fals că astfel îl folosim la putere maximă. Dar nu e aşa. Cel mai bun mod în care putem folosi timpul este făcând mai puţine lucruri, cărora să le acordăm toată atenţia şi dragostea. Trebuie să înţelegi că „timpul înseamnă bani” nu se aplică întotdeauna: nu poţi să economiseşti timp „alb” pentru zile negre la fel cum aduni monede într-o puşculiţă.

Fiecare om are un „tempo giusto” al său. Şi ştii, instinctiv, când trăieşti în ritmul tău. Simţi în oase. Eşti mai sănătos. Te simţi implicat în ceea ce faci. Te bucuri de fiecare moment. Îţi aminteşti lucrurile limpede şi nu le mai uiţi de îndată ce le-ai încheiat. Te simţi mai apropiat de oamenii care contează pentru tine. Eşti mai creativ şi mai curios. Eşti mai productiv la muncă. Ai timpul şi spaţiul de care ai nevoie să reflectezi la marile probleme ale vieţii. Te simţi plin de energie şi optimist. Eşti viu, în toate sensurile.

Cred că sursa culturii noastre tot mai accelerate este relaţia această nevrotică pe care o avem cu timpul. Îl vedem ca pe un duşman care trebuie înfrânt şi exploatat – părem a crede că cel mai bun mod în care îl putem folosi este acela de a aduna cât mai multă activitate în fiecare minut. Şi asta transformă fiecare moment al zilei într-o cursă contra cronometru. Dar nu trebuie să fie aşa.

Timpul e timp. Ceea ce contează e modul în care îl abordăm. Dacă vedem timpul ca pe un duşman sau ca pe o resursă finită care se împuţinează pe zi ce trece, atunci rămânem blocaţi pe repede-înainte. Dar dacă ne gândim că timpul este un element în care trăim, la fel ca aerul, atunci îl putem transforma într-un prieten, într-o sursă de viaţă. Un mod de-a face acest lucru este acela de a înceta să mai măsurăm timpul obsesiv. Să ne bazăm mai mult pe ceasul intern.

Timpul e timp. Ceea ce contează e modul în care îl abordăm. Dacă vedem timpul ca pe un duşman sau ca pe o resursă finită care se împuţinează pe zi ce trece, atunci rămânem blocaţi pe repede-înainte. Dar dacă ne gândim că timpul este un element în care trăim, la fel ca aerul, atunci îl putem transforma într-un prieten, într-o sursă de viaţă. Un mod de-a face acest lucru este acela de a înceta să mai măsurăm timpul obsesiv. Să ne bazăm mai mult pe ceasul intern.

Cultura mainstream este prinsă în tiparul „timpului ca duşman”. Revoluţia Încetinirii este o provocare la adresa acestei raportări, dar mai este drum lung până ce toţi vom vedea timpul ca pe un prieten.

Mai multe despre autor, aici. Mai jos, textul în original.

What time it is?

As soon as we started measuring time with clocks, we became obsessed using time as ‘efficiently’ as possible. You see that very clearly with the arrival of town clocks in medieval towns in Europe. That phrase “time is money,” which sounds so modern and seems to define the way we live in the 21st century, was actually first uttered 250 years ago by Benjamin Franklin.

Later, when our hunger to use time efficiently collided with the industrial revolution (which gave us the tools to do everything faster) and modern capitalism (which rewards speed in so many ways), we started on the path that has led to the 21st century — when every moment of the day is a race against the clock, both at work and in our private lives.

In our fast-forward culture, we have become obsessed with squeezing every last drop of productivity out of our time. This started in the workplace, but has infected our approach to free time, too. Even when we are away from work, with no deadlines and no boss hovering over us, we are still terrified of wasting time.

That means that we feel compelled to use our free time to be active, productive, doing things. If we don’t we fell guilty.

One result is that the very idea of “free time” is seen in a pejorative light. In English, people refer to it is “down time” or “dead time.”

By that I mean that we live best when we live fully, when we give our full attention to every moment and every act. We have a such a neurotic relationship with time. We see time as a bully to be feared or conquered, or as a limited resource that we must rush to exploit as fast as possible. This leads us into putting quantity before quality. We end up cramming our schedules with activity and stimulation in the false belief that this is the best way to make use of our time. It is not. The best way to use time is to do fewer things but to give them your full attention and love. You have to accept that the old adage “time is money” does not always hold true: you can’t save up time for a rainy day the way you can save up coins in a piggy bank.

Each person has their own “tempo giusto.” And you just know when you are living at the right tempo. You feel it in your bones. You are more healthy. You feel fully engaged with what you are doing. You take pleasure from each moment. You remember things clearly, rather than forgetting them as soon as they are finished. You feel closer to the people who matter to you. You are more creative and curious. You are more productive at work. You have the time and space to reflect on the big questions in life. You feel full of energy and optimism. You are completely alive.

I think the real root of our accelerated culture is our neurotic relationship with time itself. We see time as the enemy, something to be conquered and exploited to the fullest extent – we seem to think that the best way to use time is to squeeze more and more into every minute. And that turns every moment of the day into a race against the clock. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Time is time. What matters is how we approach it. If we treat time as an enemy, or a finite resource that is always draining away, then we will find ourselves stuck in fast forward. But if we think of time as the element that we live in, like air, then it can become our friend, the thing that sustains us. One way to achieve this is to stop measuring time obsessively. To rely on your internal clock more.

I think mainstream culture is still caught up in the “time as enemy” mindset. The Slow revolution is challenging that but there is still a long way to go before everyone regards time as their friend.

Citiţi şi

Cum să îți alegi pantofii potriviți în perioada sarcinii? 3 recomandări

Povestea pantofilor portocalii

Era bine să fii deșteaptă, că frumoasele sigur ajungeau niște c*rve. Și am ajuns deșteaptă

Acest articol este protejat de legea drepturilor de autor. Orice preluare a conținutului se poate face doar în limita a 500 de semne, cu citarea sursei și cu link către pagina acestui articol.