Cum pe 28 martie 2017 s-au împlinit 23 de ani de la moartea lui Eugen Ionesco, ne-am gândit să-l lăsăm să vă povestească despre întâlnirea lui cu Brâncuși…

“L-am cunoscut personal pe Brâncuşi foarte tîrziu, în cei din urmă ani ai vieţii sale, la pictorul Istrati, al cărui atelier se afla în Impasse Ronsin, chiar în faţa celui al sculptorului, despărţit de o străduţă de un metru lăţime. „Cine-i Ionescu ăsta care scrie piese de teatru?”, îl întrebase Brâncuşi pe Istrati. „Adu-mi-l într-o seară, vreau să-l cunosc”. Bineînţeles, admiram de multă vreme operele maestrului. Auzisem vorbindu-se şi despre om. Ştiam că era arţăgos, nu prea binevoitor, cicălitor, aproape crud. Îi alunga, acoperindu-i de injurii, pe negustorii sau colecţionarii care veneau să-l vadă pentru a-i propune să-i cumpere sculpturile, îi îndepărta, ameninţîndu-i cu bîta, şi pe admiratorii sinceri şi naivi care-l supărau. Existau, totuşi, cîţiva rari privilegiaţi şi privilegiate pe care Brâncuşi, neputînd trăi mereu cu totul singur, îi primea şi îi răsfăţa: aceştia sau acestea erau invitaţi să ia parte la mesele lui, în acelaşi timp fruste şi rafinate, în alcătuirea cărora intrau un nemaipomenit iaurt pe care Brâncuşi îl pregătea el însuşi, varză crudă acrită, castraveţi săraţi, mămăligă şi şampanie, de pildă. Uneori, după desert, cînd era foarte bine dispus, Brâncuşi făcea o demonstraţie de dans al pîntecelui, înaintea vizitatoarelor sale care savurau cafeaua turcească.

Am apucături rele. Acesta-i, fără îndoială, motivul pentru care nu sufăr relele apucături ale altora. Am şovăit îndelung pînă să mă duc să-l văd pe Brâncuşi: îmi era de-ajuns să-i contemplu operele, cu atît mai mult cu cît îi cunoşteam teoriile fundamentale, foarte adesea spuse celor ce-l ascultau, foarte des repetate de aceştia. Mi s-a adus la cunoştinţă ura, dispreţul lui faţă de sculptura „biftecurilor”, pe care-am numit-o astăzi sculptura figurativă, adică aproape toată sculptura cunoscută de la greci pînă în zilele noastre. Ştiam că-i era dragă formula asta şi că-i plăcea foarte mult s-o lanseze în capul oricui îl asculta. Pitorescul persoanei sale nu mă atrăgea în mod deosebit: nu mai voia să dea mîna cu Max Ernst pentru că acesta, susţinea Brâncuși, l-ar deochia şi pentru că l-ar fi făcut să cadă şi să-şi scrîntească glezna, uitîndu-se cu ură la el. Şi Picasso îl scîrbea pe Brâncuși, căci, după acesta din urmă, „Picasso nu făcea pictură, ci magie neagră”.

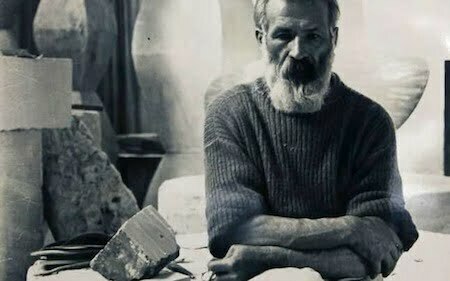

Într-o seară de iarnă, mă dusesem în vizită la Istrati. Stăteam aşezaţi în tihnă în jurul sobei, cînd uşa se deschise. Brâncusi intră: un bătrînel de optzeci de ani, cu reteveiul în mînă, îmbrăcat în alb, pe cap cu o căciulă înaltă de blană albă, cu o barbă albă de patriarh. Şi, fireşte, „cu ochii sclipind de răutate”, cum ne spune, aşa de bine zicala. Se aşeză pe un scăunel, îi fui prezentat. Se prefăcu că nu mi-a înţeles numele. Îi fu repetat, de două sau de trei ori. Apoi, arătîndu-mă cu capătul băţului :

— „Ce face la viaţa lui?”

— E autor dramatic! răspunse Istrati, care-l prevenise totuşi.

— „Ce e?” întrebă iarăşi Brâncuși.

— „Scrie piese,… piese de teatru !”

—„Piese de teatru?” se miră Brâncuși. Apoi, întorcîndu-se triumfal către mine şi privindu-mă în faţă :

— „Eu, unul, urăsc teatrul. N-am nevoie de teatru. Mă doare-n cot de teatru!”

— „Şi eu îl urăsc şi mă doare-n cot de el. Doar ca să-mi bat joc de el scriu teatru. E singurul motiv” îi spusei.

Mă privi cu ochiul lui de bătrîn ţăran şiret, surprins, neîncrezător. Nu găsi pe loc o replică destul de jignitoare. Reveni la atac după cinci minute :

— „Ce credeai despre Hitler?” mă întrebă el.

— „N-am o părere despre treaba asta” răspunsei eu cu nevinovăţie.

— „A fost un om de ispravă!” strigă el, ca pentru a-mi arunca o sfidare. „Un erou, un neînţeles, o victimă !” Apoi, se avîntă într-un extraordinar, metafizic, confuz elogiu al „arianismului”. Istrati şi soţia lui erau la pămînt. Eu nu mă urnii din loc. Ştiam că, pentru a-şi întărîtăa interlocutorii, contrazicînd ceea ce credea că este gîndul lor, îşi manifestase, rînd pe rînd, cînd ura faţă de nazism, cînd cea faţă de democraţie, de bolşevism, de anticomunism, de spiritul ştiinţific, de modernism, de antimodernism şi aşa mai departe. Închipuindu-şi, poate, că avea de-a face cu un admirator naiv, lacom de cea mai neînsemnată dintre vorbele sale, ori dîndu-şi seama că nu va reuşi să mă scoată din sărite, Brâncusi renunţă. Se lansă într-un mare discurs, cum mă aşteptam, împotriva biftecurilor ; povesti amintiri, cum venise la Paris de pe malurile Dunării făcînd o mare parte din drum pe jos ; ne vorbi şi despre ,,ioni”, principii ale energiei cosmice care străbat spaţiul, şi despre care spunea că-i zăreşte cu ochiul liber, în razele soarelui. Se întoarse către soţia mea, îi reproşa cu asprime că nu poartă părul destul de lung, apoi agresivitatea lui se linişti. Fu cuprins deodată de o bucurie copilărească, chipul i se destinse, se ridică, ieşi ajutîndu-se cu bastonul, lăsă uşa deschisă spre frig, reveni peste cîteva minute, cu o sticlă de şampanie în mînă : nu ne mai purta pică, ne simpatiza.

Îmi fu dat, după aceea, să-l revăd pe Brâncuși încă de patru sau cinci ori înainte de moarte. După ce a fost în clinică pentru a-şi îngriji un picior rupt, nu şi-a mai părăsit atelierul. Avea un aspirator, ultim model, însă cînd se afla vreo femeie printre vizitatorii săi, profita ca s-o roage să-i măture atelierul, cu o mătură adevărată. Avea telefonul pe noptieră şi mai avea un sac plin cu pietricele. Cînd se plictisea prea tare şi dorea să sporovăiască cu vecinul lui, lua un pumn de pietre, îşi deschidea uşa şi le arunca în uşa vecinului ca să-l cheme: nu-i dădea prin minte să telefoneze. Era foarte aproape de sfîrşitul lui, cînd soţia şi fiica mea care avea unsprezece ani, se duseră să-l vadă. Stătea culcat, cu căciula lui de blană pe cap, cu bastonul la îndemînă. Soţia mea e încă foarte emoţionată la amintirea acestei ultime întrevederi. Zărind-o pe fiica mea, Brâncuşi fu cuprins de o mare emoţie. I-a ţinut, pe jumătate jucîndu-se, pe jumătate sincer, un discurs de dragoste. A lăudat-o că poartă părul lung, i-a lăudat mult ochii frumoşi. Bătrînul acesta cu barbă albă îi spuse, duios, ţinînd-o de mină : „Logodnica mea mică, te aşteptam dintotdeauna, sînt fericit că ai venit.Vezi tu, eu sînt acum foarte aproape de bunul Dumnezeu. Nu trebuie decît să întind mîna să-l prind.”Apoi a destupat o şampanie ca să sărbătorească logodna.”

sursa, aici.

***

Eugène Ionesco

Some Recollections of Brancusi, translated by John Russell

It was in the very last years of Brancusi’s life that I came to know him in the studio of the painter Istrati, which stood just across the way from Brancusi’s, in the Impasse Ronsin. The passage-way between the two was barely a yard wide.

‘Who is this Jonesco who writes plays?’ Brancusi had said to Istrati: ‘Bring him along one evening. I’d like to know him.’

Of course I’d admired Brancusi’s work for a long time. I’d also heard people talk of the man himself. I knew that he was a cantankerous old person, not easy to deal with, always grousing, a sort of wild man, almost. Dealers or collectors who came to call in the hope of buying one of his sculptures would be insulted and driven from the door, it seemed. But as Brancusi could not live entirely alone there were just a few privileged friends, women as well as men, whom he would welcome and make much of. They it was who were invited to share in his at once primitive and fastidious meals — meals at which the menu might well include an extraordinary yoghourt prepared by Brancusi himself, some cabbage (raw, and bitter to the taste), some salted cucumbers, polenta, and champagne. Sometimes, after the dessert, if he was in a particularly good humour, Brancusi would give a demonstration of the danse du ventre, while his lady-guests sipped their Turkish coffee.

I have a difficult character and, doubtless for that reason, I detest those of whom the same could be said. For a long time I hesitated to go and see Brancusi: it was enough for me to look long and closely at his work, more especially as I knew the basic theories which he was very fond of expounding to his guests, and which they were no less fond of expounding to others. I knew how he hated and despised what he called ‘beefsteak’ sculptures — figurative sculpture, as it would now be called: more or less everything that has been done in sculpture from the time of the Greeks to the present day. I knew that this was a favourite gambit of his, and one which few visitors were spared. Nor did his eccentricities much attract me: he refused, for instance, to shake hands with Max Ernst, claiming that Ernst had the evil eye and had caused him, with one hate-filled glance, to fall down and break his ankle. Nor could he bear Picasso:

‘Picasso is not a painter at all, but a black magician.’

One winter’s evening I went to call on Istrati. We were sitting quietly talking round the stove when the door opened. Brancusi came in: a little old man of eighty, with a big stick in his hand, dressed in white with a tall cap of white fur on his head, a patriarchal white beard and, of course, ‘eyes sparking with malice’, as the formula so aptly has it. He sat down on a stool, and I was introduced. He pretended not to have heard my name, and it was repeated to him twice, perhaps three times. And then, pointing his stick at me, he said:

‘What does he do for a living?’

‘He’s a dramatist!’ said Istrati, who had already explained this more than once to Brancusi.

‘He’s what?’ said the Master.

‘He writes for the theatre . . . plays, you know!’

‘Plays !’ Brancusi was dumbfounded.

And then, turning towards me in triumph and looking me full in the face:

‘Well, I detest the theatre. I don’t need the theatre. I abominate the theatre!’

‘I detest it, too. Detest it and abominate it. That’s the only reason why I write plays — to make a monkey of the theatre.’

Astonished and disbelieving, Brancusi looked at me with his sly old peasant’s eye. For the moment he couldn’t think of anything sufficiently offensive to say in reply; but, five minutes later, he came back to the charge.

‘What did you think of Hitler?’ he asked.

I replied quite franky that that was a subject on which I had no opinion.

‘He was a capital fellow!’ Brancusi burst out, as if to challenge me. ‘A hero, a man misunderstood, a victim!’

And he went off into an extraordinary, confused, metaphysical eulogy of ‘Aryanism’.

Istrati and his wife were horror-struck, but I didn’t turn a hair, for I knew that Brancusi liked to disconcert whomever he was with by saying the exact opposite to what he supposed them to believe. In this way he had been known to launch full-scale attacks successively on the Nazi party, democracy, anti-communism, science, modernism, anti-modernism . . .

In the end he gave up: whether because he took me for an ingenuous admirer who would take his every word as gospel, or because he realized that he would never manage to touch me on the raw, I cannot say. He made the great anti-beefsteak oration for which hearsay had prepared me. He told us stories of his past—how, for instance, he had once walked most of the way from the banks of the Danube to Paris. He spoke of the ‘ions’, those space-traversing principles of cosmic energy which he could see with his naked eye, so he told us, in the rays of the sun. He turned to my wife and reproached her severely for not wearing her hair longer. And then he suddenly seemed to run out of aggressivity. A childlike joy came over him, his face relaxed in smiles, he got up, went out of the room leaning on his stick, left the door open to the cold, and came back after a minute or two with a bottle of champagne in his hand. He wasn’t against us any more: he was beginning to like us.

I was fortunate enough to see Brancusi four or five times again before he died. After he had been in a clinic to have his fractured leg looked after, he never left his studio. He had the latest model of vacuum cleaner, but whenever a woman was among his visitors he asked her to sweep the studio with a real broom. He had the telephone, on the table beside his bed, and he had a bagful of pebbles. When he got too bored and wanted to talk to his neighbour he took a handful of the pebbles, opened the door and threw them, by way of summons, at Istrati’s front door. It never entered his head to telephone.

He was very near his end when my wife and my daughter, who was then eleven, went to see him. He was in bed, with his fur cap on his head and his big stick within reach. My wife is still deeply moved when she thinks of this last interview. When Brancusi saw my daughter he fell into a state of great emotion and made her, half seriously and half in make-believe, a declaration of love. How right she was to wear her hair long! What beautiful eyes she had! The white-bearded Ancient took her by the hand and said with great tenderness: ‘My dear little betrothed, my fiancée, I have been waiting for you all my life. I am happy that you have come. As you see, I am very close to our good Lord now — I need only stretch out my hand to catch hold of Him.’

Then he opened a bottle of champagne to celebrate the betrothal.

Citiţi şi

Brâncuși: Eu mă hrănesc printre străini ca la Gorj

Peggy Guggenheim: “Cumpăr o lucrare de artă pe zi și trăiesc la maximum”

Stelian Tănase – De ce nu mai vor venețienii turiști

Acest articol este protejat de legea drepturilor de autor. Orice preluare a conținutului se poate face doar în limita a 500 de semne, cu citarea sursei și cu link către pagina acestui articol.